I was standing in line for coffee this morning with a group of people who were obviously in town for the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival Presented By Shell when I got to overhear yet another, "So what is chicory, anyway?" conversation. Usually when they ask this they want you to give them some canned performance built around some combination of these frequently-in-dispute factoids.

Many myths surround the use of chicory in coffee blends. One story holds that the root was accidentally found to be a flavorful additive to coffee as far back as the sixteenth century. Chicory is made from the root of the endive plant and was used as a filler and flavor enhancer in parts of northern Europe at least as far back as the eighteenth century. Napoleon's armies reportedly brought chicory back to France, where Parisians began to prefer its taste and the thriftiness of adding chicory. Since chicory could be grown in parts of Europe where coffee could not, the root was obviously cheaper. How it made its way to the United States is unknown. For many years it was used to stretch coffee supplies, especially in hard times such as the Civil War. This practice upset many purists, who disdained chicory and other additives. Somewhere along the way, however, New Orleanians developed a taste for chicory in coffee blends and many prefer it today. Throughout the New Orleans area, chicory has been used as a flavor additive. Local coffee companies have kept up with demand by offering the same blends with and without chicory. Within the city, coffee and chicory are consumed in greater quantities than anywhere else. Outside of the city, most coffee drinkers imbibe pure coffee instead.You can arrange this any way you like to suit whatever story you feel obligated to tell. Here's a slightly different version, for example.

Chicory was first roasted and used in coffee in Holland around the year 1750. In a short period of time, it became a popular replacement for coffee. By 1785, James Bowdoin, the governor of Massachusetts had first introduced it to the United States. In 1806, Napoleon attempted to make France completely self-sufficient. To eliminate coffee imports, chicory was used as a complete substitute. While this system did not last more than a few years, the French continued to use chicory to blend with their coffee. This practice would migrate to the still French-influenced New Orleans and is still considered the normal New Orleans-style of coffee.Or slightly different again.

One historical and cultural example of chicory's use as a coffee substitute is found in New Orleans. Due in part to its influences from French culture, New Orleans was a major consumer of coffee prior to the Civil War. Then, in 1840, coffee importation to the New Orleans harbor was blocked. Taking a cue from their French roots, locals began to use chicory as a coffee substitute. Today, chicory remains a popular coffee replacement or coffee flavoring in New Orleans, and 'New Orleans Coffee' typically refers to chicory coffee. New Orleans coffee vendors often blend their coffee with up to 30 percent chicory root.

So, depending on which resourceful, embattled, thrifty people you feel like romanticizing, the basic story is it's a root used as an additive to stretch coffee. Or make it taste better... or worse... again depending on the point of view of the storyteller.

In any case, it's definitely one of the more tiresome things tourists will ask you about and expect you to dance for them in the telling. But rather than just start punching people in the face I'm looking for new and less boring lies to tell them. Here's my new one. You see "chicory" isn't a root at all. Instead it's the flavor enhancing byproduct of this process.

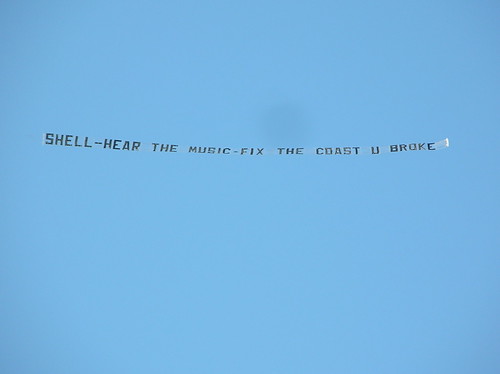

The company, Houston-based W&T Offshore, admitted its workers had used coffee filters in October 2009 to clean oil and other minerals out of the water byproduct discharged overboard from their platform in the Ewing Banks 910 lease block, about 65 miles south of Port Fourchon.We already know how much the oil industry enjoys describing contamination in food metaphors. Why not throw another one in there? At least this one is appropriately bitter which is bound to fit the mood of anyone whose had to pay the consequences of bucking such a system.

They were filtering the oil out of the water samples that were sent into a lab and recorded with the federal government.

Meanwhile, the water they were dumping back into the Gulf on a constant basis stayed contaminated.

“When you’re in the offshore industry if you want to get along, you better go along,” said Randy Comeaux of Lafayette, who was a contract employee assigned to W&0T platforms in 2009. “And what happens offshore stays offshore. You break any one of those two rules, in one fashion or another, you will not be working offshore.”Comeaux maintains a blog on Examiner.com where he writes about offshore drilling hazards such as, well, naturally, the kinds of food additives produced.

Comeaux says he’s one of the few who doesn’t simply “go along,” and he’s paid the price. He said he’s been fired multiple times for reporting violations and can’t get a job offshore because of it.

The produced water with the chemicals is then discharged overboard into the gulf of mexico waters. This produced water is basically salt water , the chemicals are now hazardous waste which can only be discharged in limited quantities, to allow the gulf waters to break them down with time .

Fish , shrimp , crabs , oysters and a large multitude of seafood life swim in these contaminated waters around the offshore platforms consuming these contaminants.

These fish , shrimp , crabs , oysters and other seafood are then consumed by the people along the gulf coast and the entire US.

This is why it helps to look to our plucky ancestors for inspiration in times of hardship. Better to just make lemonade rather than worry about what's gone wrong with the lemons. In the next century maybe our descendents in the New Orleans Islands could be standing in line at the seafood automat fielding questions from tourists about the origins of the locals' peculiar love of Corexit as a condiment. Probably we'll tell them it adds aroma or something.

1 comment:

One of the things I've learned in grad school is the necessity of taking academic research and introducing it to a layman audience.

For example, here's one from Tulane for you to chew on:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22504303

Lung epithelial cell death induced by oil-dispersant mixtures.

Wang H, Shi Y, Major D, Yang Z.

Source

Department of Global Environmental Health Science, School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA. hwang2@tulane.edu

Here's a Prezi presentation on it:

http://prezi.com/yxr2jzkm926u/human-toxicity-and-oil-dispersant-mixtures/

Post a Comment