Here's hoping they had a lot of fun Monday at the inaugural thingy. If you were unable to capture the magic in person, it has been archived for you here.

The Lens is doing a thing where you, the reader, can fashion yourself a participant in the drama of online journalism and vote for which of a few selected statements you would most like to see them "fact check." Ideally they would just go ahead and check any and every statement they deemed at least suspicious enough to ask us about. The five they've highlighted seem like an obvious good start. But the Mayor said a bunch of other strange things too which I'd like to see addressed.

You can review the full text of his speech here. Although, I would also recommend scrolling back through WWLTV reporter Paul Murphy's tweets. They do a nice job of stripping the speech down to its essential random aphorisms. From among these, I've collected a few write-in candidates The Lens can add to their fact-check poll.

1) "We can become a shining city on the hill"

Which hill is he talking about? Most New Orleanians can name only one and it is not a naturally occurring hill. Also, it's probably worth pointing out that had Bienville put New Orleans on a hill in the first place a lot of the stuff we worry about today wouldn't be a problem.

2) "There is hope, a new way"

I am not so sure the way we're onto at the moment is all that new. I'd like to hope but something tells me not to. At least not until the hope is fact checked.

3) "We can create the New Orleans we always dreamed of"

Thanks to something a previous Mayor talked about once, I have occasionally dreamed of a New Orleans that is made out of actual chocolate. I don't know that we can create this place.. or even if we should.

4) "We all must move forward together"

I suspect we can probably move in several different directions at different times. Mitch says otherwise but I've seen him line dance and it's not all that coordinated.

5) "Today is first day of the rest of your life"

Please tell me I can still put this off until tomorrow.

After the celebration, though, there's plenty stuff to do.

The mayor will take his oath of office Monday at the Saenger Theatre and then go back to fighting on both the expenditure and the revenue fronts, trying to hold off big potential bills due on the city’s jail and firefighters pension fund while also pushing the Legislature to at least give voters in New Orleans the option of raising taxes on hotels, cigarettes and their property.The tobacco tax isn't doing so well. (Update: It has now failed)

As for the hotel/motel tax, things are complicated. Last week, the mayor's proposed 1.75 cent increase ran into heavy opposition from gubernatorial candidate Jay Dardenne as well as from the lodging industry's taxpayer funded (via the Convention and Visitors' Bureau) publicity arm, NEWORLEANSWILL.

The hoteliers insist they're too busy trickling down minimal wage and benefit service industry jobs on the city to contribute anything significant to solving its financial problems. The great majority of the current hotel/motel tax goes to state entities geared toward servicing the hospitality industry. Last year, in fact, the industry asked for and was granted the option of paying a "voluntary" 1.75 percent tax provided all of that money went directly back into its own marketing efforts.

The mayor has a second proposal in his back pocket which would ask the legislature to create a special taxing district where, theoretically, all of the tax revenue from retail and hotel taxes would accrue to the city. It was believed the targeted district would include the redeveloped World Trade Center site but negotiations over that project abruptly fell apart last week reinforcing the impression that this is a taxing district to nowhere.

More curiously, the preliminary draft of the bill authorizing the new district appears to give governing authority to the Louisiana Stadium and Exposition District board which itself is already funded by the current hotel/motel tax. The board would, apparently, also have the authority to add properties to the special district as it sees fit. Why would LSED be asked to make decisions which appear to route tax revenue away from itself? The answer currently is that the draft is just a "placeholder bill" whose wrinkles are expected to be ironed out later. If it moves, it will be worth watching.

Meanwhile with the tobacco tax not going anywhere and the hotels refusing to budge, the Mayor is asking homeowners to take up the slack. And it's a lot of slack.

With two of his tax increase proposals on life-support, Mayor Mitch Landrieu has doubled down on a third option that would raise property taxes in New Orleans to help pay for more police officers, improvements to the parish prison and the city's debt to the firefighters' pension fund.Tourism leaders who loudly proclaim their essential role in the city's economy are refusing to contribute anything to its tax coffers that doesn't come directly back to them while residents are being asked to double their burden just to keep up basic services.

Through an amendment Thursday (May 1) to House Bill 111, the administration asked a state Senate committee to double two millages for police and fire protection from 5 mills to 10 mills each. The move could generate an extra $30 million a year for the cash-strapped city.

Even the Monopoly man thinks this is backwards.

But backwards would appear to be the new black when it comes to urban development policy these days. Planned gentrification is all the rage. Sociologist David Madden writes about this frequently. The following is from an op-ed published in The Guardian last year.

Here's how gentrification talk typically goes: poor neighborhoods are said to need "regeneration" or "revitalization", as if lifelessness and torpor – as opposed to impoverishment and disempowerment – were the problem. Exclusion is rebranded as creative "renewal". The liberal mission to "increase diversity" is perversely used as an excuse to turn residents out of their homes in places like Harlem or Brixton – areas famous for their long histories of independent political and cultural scenes.

After gentrification takes hold, neighborhoods are commended for having "bounced back" from poverty, ignoring the fact that poverty has usually only been bounced elsewhere.

In an insidious way, the narrative of "urban renaissance" – the tale of heroic elites redeeming a city that had been lost to the dangerous classes – permeates a lot of contemporary thinking about cities, despite being a condescending and often racist fantasy.

Removing the poors and replacing them with a better sort of resident is not merely an unfortunate side effect of modern economic development, it's often the explicit policy goal.

Evangelists for elite-dominated urbanism sometimes argue, as New York's mayor Michael Bloomberg did recently, that attracting the super-rich is the best way to help those city-dwellers he quaintly calls "those who are less fortunate". But the trickle-down argument for gentrification ignores the fact that the "very fortunate" invariably seek to bend municipal priorities and local land uses towards their own needs, usually to the detriment of their less powerful neighborsNew York and San Francisco are the most frequently cited examples of what elitist urban policy has done to formerly working class neighborhoods. But the phenomenon is not isolated only to those places.

Thomas Frank has written a lot lately about urban planning's obsession with creating "vibrancy" via manufactured arts and culture scenes although no one is really sure what that means much less can delineate its benefits.

How does art do these amazing things? you might ask. Reasoning backwards from the ultimate object of all civic planning—attracting and retaining top talent, of course—the Art-Place website pronounces thusly:The ability to attract and retain talent depends, in part, on quality of place. And the best proxy for quality of place is vibrancy.Others have spelled out the formula in more detail. We build prosperity by mobilizing art-people as vibrancy shock troops and counting on them to . . . well . . . gentrify formerly bedraggled parts of town. Once that mission is accomplished, then other vibrancy multipliers kick in. The presence of hipsters is said to be inspirational to businesses; their doings make cities interesting and attractive to the class of professionals that everyone wants; their colorful japes help companies to hire quality employees, and so on. All a city really needs to prosper is group of art-school grads, some lofts for them to live in, and a couple of thrift stores to supply them with the ironic clothes they crave. Then we just step back and watch them work their magic.This, then, is how far it’s gone. The vibrant is the public art of today. It is Official. Our leaders think it will solve the problems of the cities large and small. Our leaders believe it will help to pull us out of our persistent economic slump.

If you have time for it, here is a remarkable conversation between Frank and Lewis Lapham where they talk about a number of things including the institutionalized co-opting of perceived "coolness" for the purposes of consumer branding. Here Frank addresses this specifically with respect to urban revitalization schemes.

..there are cities all over America now that are investing heavily, both of their own money and with foundation money — public-private partnerships — in the idea of planned bohemias. You know about this? (Laughs) Potemkin bohemias, fake bohemias that a given city will set up. They will hire some consultant in coolness. And he’ll come and tell them how to make a neighborhood “cool.” And the reason why you would want to make a neighborhood cool? Why do you want to do that? Well, of course, in order to attract and retain top corporate talent. Get Boeing or some other big corporation to move to your town, because it’s got all these hipsters in it. We used to joke at The Baffler Magazine, “Boeing moved to Chicago because we were there.” Everything that Mayor Daley was claiming credit for. No. We were doing it. We’re the ones who were responsible. Because my friends and I were so goddamn cool in those days. By the way, this fake bohemia thing really happens. People waste tons of money on it.In New Orleans we love to fight the "hipster" wars. Or, at least, we love to proclaim our exasperation with the whole conversation. "What even is a hipster?" sigh so many so often as they miss the point. "Wouldn't you rather have (INSERT HIPSTER CLICHE OF CHOICE... ARTISINAL TOAST, PERHAPS) than blighted neighborhoods? What is it about (TOAST) that so frightens xenophobes like you?"

But no one is afraid of toast, or kale, or empanadas or whatever the thing may be. People do get squeamish about being priced out of their homes in the name of "blight reduction" though. Among the mayor's statements The Lens offers to fact-check for us is this.

In four short years, we went from having the worst blight problem in America to tearing down or fixing up blight faster than anywhere else in the country.I would urge readers not to vote for this to be the fact-check item. For one thing, they already did fact check it. For another, fixating too much on "blight" as a bug-a-boo plays directly into the canard that "fighting blight" is such an urgent priority that we must accept gentrification as its necessary alternative.

Here is a worthwhile essay by geographer Tom Slater which attacks the notion of gentrification vs. blight as a "false choice."

In order to situate gentrification in a more helpful political and analytical register, we must blast open this tenacious and constrictive dualism of “prosperity” (gentrification) or “blight” (disinvestment) by showing how the two are fundamentally intertwined in a wider process of capitalist urbanisation and uneven development that creates profit and class privilege for some whilst stripping many of the human need of shelter. No viable alternatives to class segregation and poverty will be found unless we ask why there are neighbourhoods of astounding affluence and of grinding poverty, why there are “new arrivals” and an “Old Guard”, why there are renovations and evictions; in short, why there is inequality.

Despite many attempts to sugarcoat it and celebrate it, gentrification, both as term and process, has always been about class struggle. When we jettison the ludicrous journalistic embrace of “hipsters", reject the political purchase of the enormous literature on the gamut of individual preferences and lifestyles of middle-class gentrifiers, and consider instead the agency of developers, bankers and state officials, then questions such as for whom, against whom and who decides come to the forefront - and we can begin to see false choice urbanism as both red herring and preposterous sham

Leaders make deliberate choices affecting the availability of affordable housing, the funding of infrastructure, and the distribution of the tax and fee burden for services. These are political decisions, of course. But we are expected to presume they come to us as benign technocratic solutions judiciously engineered by apolitical experts in some sterile policy lab. No such place exists. Policy choices create winners and losers. In order to at least try and calibrate those choices to best fit the will of the majority rather than that of the elite, we elect our policymakers democratically. And still we very frequently manage to get it all wrong.

During Mitch Landrieu's term as Mayor, New Orleans has become a nexus of trendy elite urbanist theory. Partly this is because we've been tasked with the nation's biggest and most unique rebuilding job at a time when neoliberal trends have come into ascendance. But it's also the case because Mitch just chooses to buy into a lot of it.

Landrieu is a regular at the Aspen Ideas festival of elite consensus where he talks about favorite topics like school charterization and "public-private partnerships" with Goldman Sachs executive Lloyd Blankfein and media parasite Ariana Huffington and the like. He tours the country as a sort of national poster-child for neoliberal urbanism touting a "New Orleans miracle" in the same manner a somewhat less cogent Bobby Jindal is hawking a "Louisiana Miracle" in the course of his proto-campaign for President.

In a sense, neither of them is wrong to say that the city and state have experienced boom times as of late. The state has seen low unemployment numbers in recent years thanks the nation's thirst for fossil fuels. The state has failed to reap the benefits of the oil and gas boom, though, as its finances are still an unholy mess while its infrastructure, health care and education services.. not to mention its coastline... continue to crumble.

Similarly the City Of New Orleans has been putting federal disaster recovery dollars to work rebuilding... well... everything at once.

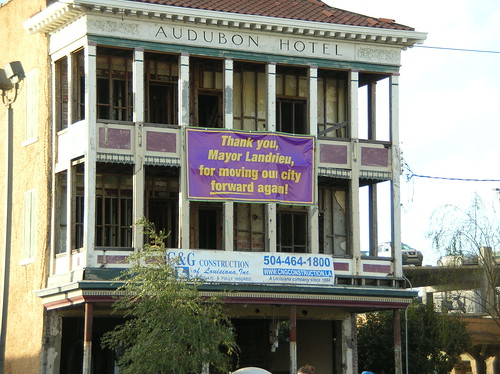

When he took office in 2010, Landrieu adopted a “fix everything at once” approach to New Orleans’ myriad problems. Crime, blight, potholed streets, leaky sewerage, joblessness, homelessness — he said we had to tackle them all at the same time.Moseley kind of suggests in that column that a "fix everything at once" strategy might have been imprudent. But I'm not sure there was any alternative. The imperative of post-Katrina rebuilding more or less dictated a crane on every skyline once the money started rolling in. There's no reason to fault Landrieu for simply allowing federally funded rebuilding projects to proceed. A better criticism asks, as Slater puts it, "for whom, against whom" New Orleans has been "fixed."

It was an ambitious strategy, to be sure, but the Landrieu administration seemed to sense it was necessary.

Without rapid improvements on all fronts, they feared, the city wouldn’t expand its tax base quickly enough to shoulder old debts and expensive new consent decree obligations.

Without quick growth, the administration feared we’d be revenue-starved and forced into a vicious circle of budget cuts, decreased services, and further population outflows.

In fact, Moseley does address this question, and this is really the crux of his column so here it is.

Critics are displeased and urge Landrieu to make budget cuts rather than confiscate more income from taxpayers. Landrieu’s allies say the mayor needs the tax revenues for budget “flexibility.” But giving the administration more flexibility comes at the expense of increasingly inflexible household budgets.But it's imprecise to say simply that the problem is we're looking to "transplants" to expand the tax base. More to the point, we're looking to big money buyers (granted, mostly from out of town) to radically bid up housing prices.

Another problem with Landrieu’s approach is that we’re expanding the tax base with an influx of transplants, a dynamic that has ignited housing inflation and a sharp increase in rents.

But what was once a leisurely inspection has become, in some cases, a feeding frenzy. Agents now bring their clients in tow. Offers are sometimes discussed outside; agents describe offers being scribbled out on the hoods of cars.It's hard to imagine a sale like that going through solely for the purpose of maintaining an existing rental property. New Orleans, particularly in its historic neighborhoods, is an investment now. The wage earners and rent payers have to be moved out of the way in order for the asset traders to flourish.

Last week, one of the properties open on the tour was 1015 Arabella St. -- a double being rented out to tenants. By Friday morning, the listing agent, Lynne Ann Fowler of Latter and Blum, said the owner had received three offers and already accepted one that was "close" to the asking price of $375,000, although she said she couldn't say the exact offer while the contract is pending.

She said the house is in need of some renovation, depending on whether the new owners want to convert it to a single and live in it, or keep using it as rental property.

This shouldn't come as a surprise. Renters and wage earners have become more or less structurally irrelevant people over the past 20 or 30 years. Going back as far as the late 1970s, as automation and globalization began to seriously affect the manufacturing sector of the economy, wages became uncoupled from productivity meaning a great deal of wealth could be produced while wages remained largely stagnant. Again, I'll refer you to that conversation between Lapham and Frank for some insight as to what happened next.

as long ago as 1985 or 1986, the money earned in the United States, the income earned from wages on one hand and income earned from rents which would be real estate, stocks, dividends and interest — together they’re considered rents. But the first time in the history of the United States, either in 1984 or 1985, that rentier income surpassed the income earned from wages. And we are developing right now a really, an extremely opulent rentier class. If you think of the profits that have been made in the stock market in the last 30 years and you think of the compound interest, that is why you now have apartments selling for $95 million. So we are getting a rentier class. There’s no question about that. The numbers are all there.If you aren't a member of a highly specialized profession or some sort of asset speculator... in other words, if you're not a part of what Mitch Landrieu euphemistically calls the "knowledge economy" there really isn't much of a place for you.

These kinds of economic challenges are, of course, much bigger than New Orleans. They are born of long term trends and are international in scale. The fact that they are being felt as acutely as they are in New Orleans today is probably a perversely healthy sign as much as anything. It means that the focus of the global economy is on us. Unfortunately, the global economy also happens to be kind of terrible.

Still, it matters how we react politically to these events in the little local space where our voices might make some small difference. Of course, we react poorly. In what has more or less become the consensus view, the city's "changing demographics" represent a change for the better. Many seem to believe the city cannot gentrify fast enough.

This consensus holds that the poor and working class of "old" New Orleans were themselves the primary cause of the city's ills. In a recent documentary, developer Pres Kabacoff called them a "drag on the economy."

Last week, in his Uptown Messenger column, real estate agent Jean-Paul Villere sneered at the supposed apathy of "old" New Orleans he saw manifested in a broken phone booth that had not been hauled away expeditiously enough for his taste. And yet he cautiously holds out hope that, with a little more "new blood" we'll get our act together.

Right now people, we’re serving our clients (read: ourselves) poorly. Because there’s always a reason to do or not to do something. And while people can rationalize anything, your job is still your job, and if it’s worth doing, then it’s worth doing well, yes? With all this new blood pouring into the Crescent City, between the entrepreneurial set, Hollywood types, and medical practitioners, my hope is the ‘not my job’ culture can be fixed along with all the other deficiencies we too often mistake for charm or endearment. But I’m not convinced. Yet.How many doctors, entrepreneurs, and "Hollywood types" does it take to haul a pay phone off to the dump? I can't wait to find out either.

In the meantime, though, I'd rather ask what explains all this downward looking class hostility? To answer that, we look once again at how what's left of our middle class has been badly abused by the decline of the wage-based economy. And at the deliberate manipulations of the social compact designed to divide and conquer them politically.

Simply put, starting in the 1980s policymaking elites in the Western world were scared to death of oil shortages, inflationary spirals and the impact of jobs being shipped to lower-wage nations or made obsolete by increasingly powerful machines and computers. Something had to be done. Even as foreign policy became explicitly focused on securing access to oil, domestic policy became focused on quashing inflation while disguising wage stagnation. Either countries needed to move sharply to the left through increased worker protections and redistribution of incomes, or to the right by substituting an asset-based economy for the old wage-based economy. Most chose to go right — an understandable move at the time given that state Communism was still a threat to capitalist economies, but also a spent and discredited ideology. Ronald Reagan best made the case for the new economic model in a speech from 1975:This was accomplished in a number of ways. The short of it, though, is that middle class life in America had less to do with communal interest institutions like, say, labor unions, or defined-benefit pensions. Instead our middle class began to see themselves as isolated mini-capitalists with 401(k)s, lines of consumer credit, and most likely a home mortgage which, although not purely a speculative investment for most people, at least provided them with a simulation of that experience.

Roughly 94 percent of the people in capitalist America make their living from wage or salary. Only 6 percent are true capitalists in the sense of deriving income from ownership of the means of production …We can win the argument once and for all by simply making more of our people Capitalists.One of the chief ways that American and British policymakers put this vision into reality was by crippling organized labor. But while that certainly placed downward pressure on wages in the U.S. and Britain, labor was not so similarly affected in most of the rest of the developed world. Organized labor remains a powerful force throughout most of Europe, yet growing wealth inequality and a declining middle class are present trends there as well. The health of organized labor abroad has helped stem the tide, but has not managed to stop it. The less noticed but potentially more consequential way that policymakers across the industrialized world set about accomplishing this goal was to push their middle classes to invest their wealth into assets, especially stocks and real estate, then use the levers of public policy to inflate the values of those assets in order to disguise the inevitable declines in wages.

Those who buy into this illusion are invited to view the people around them as competitors rather than neighbors. When we imagine ourselves as individual entrants in a pageant of capitalistic virtue, we are quicker to jettison those deemed a "drag" or at least to wish their sloth rehabilitated through exposure to superior examples of character. Thus J-P Villere can demonstrate his industriousness by tweeting a photo to Entergy while he awaits the coming his professional brethren to further enlighten the rest of us.

As the shock of each busted asset bubble puts more and more strain on a middle class striving to maintain its illusions, these anxieties only get worse. White collar skills previously thought to be safe prove as easily obsoleted by technology and globalization as the blue collar base that went before. Housing prices crash, those 401(k)s haven't earned as well as advertised, long term career employment becomes less certain and suddenly everyone is an "entrepreneur."

And still our leaders completely miss the point. In his inaugural address Monday, Mitch Landrieu touted New Orleans as "a vibrant hub for young entrepreneurs." Despite how ominous that sounds in light of everything, he meant it in a good way.

While it's fine for the mayor to act as the city's booster-in-chief, it's important to note that the proliferation of "entrepreneurial innovation" he's celebrating can also be a sign of distress.

Some of these new companies are obviously helpful to the economy. But when you look at the kinds of businesses getting started, and who is starting them, it becomes clear that lots of entrepreneurship in the last few years has been symptomatic of our sick job market.This is most especially a concern when it comes to the entrepreneurial activity that takes place within what is now known as the "sharing economy."

A huge precondition for the sharing economy has been a depressed labor market, in which lots of people are trying to fill holes in their income by monetizing their stuff and their labor in creative ways. In many cases, people join the sharing economy because they've recently lost a full-time job and are piecing together income from several part-time gigs to replace it. In a few cases, it's because the pricing structure of the sharing economy made their old jobs less profitable. (Like full-time taxi drivers who have switched to Lyft or Uber.) In almost every case, what compels people to open up their homes and cars to complete strangers is money, not trust.New Orleans does not have Uber or Lyft yet but it does produce a lot of action on Airbnb. An extensive feature on Airbnb's local impact ran in the March issue of Antigravity. While the service can seem like a godsend to marginalized homeowners struggling to keep up with bills, in the aggregate it's yet another constricting force acting on the housing market.

For one thing, it puts renters in New Orleans into direct competition for space with an endless churn of visitors able to pay $50 to $200 a night. For another, it subjects residential neighborhoods to wave after wave of super-short-term outsiders, a potent disruptive and destabilizing force in areas still fighting their way back to some semblance of stability. Tourists have no understanding of the neighborhoods they’re invading, and unlike longer-term residents, they have no incentive to get along with or respect those who live in the neighborhood. They’re here to party and enjoy themselves, and it’s in the Airbnb host’s economic interest to ensure they’re able to do so. On a NOLA.com article about the city’s ongoing failure to enforce the laws against illegal short-term rentals, one commenter said his experience of living next door to an illegal guesthouse was like “living next to a frat house.”

Also at issue, from the city's perspective, is the potential for lost revenue. After all Airbnb is basically one big off-the-books hotel. The city welcomed a near-record 9.28 million visitors last year. A key challenge for the mayor and his new council faced with a severe budget crisis is figuring a way to capture the highest possible revenues from the city's most vital industry.

The hotel/motel tax hike is already meeting with significant static in the legislature. I can't help but wonder, then, if this might help explain the dramatic rise proposed for property taxes. Think about it. The housing market in New Orleans is on fire right now. A lot of the pricier properties are already part time second homes. A lot of property owners are getting into the illegal short-term rental business. It could be that the idea here is to pay off the consent decree and fire pensions by indirectly taxing this off-the-books activity.

If this is what they're thinking, I have to admit it's kind of ingenious. Leaving the illegal rental market alone keeps the real estate market hot. This means more house flipping, less blight, and, as neighborhoods seek to cultivate more tourist-friendly amenities, it means more "vibrancy." The city can reach its goal of 13 million annual visitors and not one extra cent in hotel taxes need be raised. It basically hits all of the Landrieu sweet spots and takes a fiscal load off the city's back in the process.

Of course that for whom, against whom question remains troublesome. Rents, utilities, and other fees continue to rise. "Old" New Orleanians will have to stretch their entrepreneurial acumen to its limits in order to keep up. In his speech Monday, Mayor Landrieu appeared to acknowledge some responsibility to do something about that.

Our mission is to create a City of peace where everyone can thrive and no one is left behind.So far, we haven't done much.

Four years from now may seem a long way away, but time flies.

Those 1460 days will pass in a second. And what will we accomplish in our short time together?

What will we have done to open the circle of opportunity and prosperity to all?

As noted above at some length, economic inequality is not a problem unique to New Orleans and certainly the mayor's capacity to solve it is limited. Economist Thomas Piketty has prescribed a Global Wealth Tax as his preferred policy response. Mitch can't even get an 80 cent tobacco tax passed in the Louisiana Legislature.

"What will we have done to open the circle of opportunity and prosperity to all?" Mitch now has fewer than 1460 days to answer his own question. Today is the first day of the rest of those.

3 comments:

A tour de force. This is the best example I've ever seen of the devastating effect which can be achieved through the use of witheringly restrained language coupled to a deep intelligence reflected at every turn in an unblinking panoramic survey of an issue influencing the broadest social and economic landscape of modern urban life. Other than that, ain't much.

Great job

Fantastic post Jeffrey. Bravo!!

Post a Comment