Source: The Data Center: "Who Lives In New Orleans Now?" 2018

Urban development policy in New Orleans is a confederation of schemes to enrich the few at the expense of the many and people are starting to catch on. It remains an open question, though, whether we're going to demand better of our political decision-makers or if we're going to continue accepting the same approach indefinitely as long as the hollow rhetoric supporting it is updated every once in a while to co-opt the political concerns of the moment.

In Monday's Advocate, we found a pretty typical example of one such branding adjustment. "New Orleans's incentives for developers aren't serving the city," says the headline. That sounds true enough. Unfortunately, this is a story about what a consultant's report commissioned by the Landrieu Administration to evaluate those "incentives" has to say about them. What might such an outfit tell us needs to be done? Well, of course, we have to make slight cosmetic changes to the process by which we award those same incentives to the same developers. Problem solved.

Instead, the report — prepared by the national consulting firm HR&A Advisors — recommends that officials issue tax breaks or other subsidies, under four major incentive programs, to firms that earn high scores on a new scorecard aligned to city priorities.Great. A "points" system. Look, regardless of whatever gimmick they decide to glom on to their let's-shovel-money-to-developers device, it is still, first and foremost, a plan to shovel money to developers. It is still substituting carrots where there should be sticks.

“If you are building affordable housing in a high-opportunity neighborhood, you could get more points for that,” said Ellen Lee, the city’s director of community and economic development. “So you would ultimately get more subsidy.”

Developers also could get high scores for incorporating sustainable building practices or for exceeding the standards of the city's policies on local hiring, aiding disadvantaged business enterprises or paying "living wages."Where there ought to be strict enforcement of mandatory environmental, equity and labor standards, there are "high scores" for incorporating and aiding but not necessarily always complying with such practices.

For decades, municipal governments have overseen a trickle-down process by which public money is directed through various tax abatement programs to finance construction of private for-profit real estate development. These special privileges are hilariously labeled "incentives" by the same free market fundamentalists who otherwise lecture us that government has no place in the natural and perfect resource allocation function of unfettered capitalism. In these cases, though, we are told that distorting the market with gifts to real estate oligarchs is really in the public interest. For some reason we're told publicly financed kickbacks are the only way to save our most iconic buildings from "blight" or to put even the most valuable real estate in all of Louisiana "back into commerce."

It is only recently that this rationalization has expanded to include a sop to the affordable housing crisis. And even then, the reasoning is flimsy as hell. Regardless of how many "points" a residential development accrues setting aside a token number of units that meet a dubiously defined threshold for affordability, the main thing we are doing is putting public investment into building nice things for rich people.

Construction has begun on the Odeon, a $106 million, 271-unit apartment building that will include 12,000 square feet of retail in the Central Business District, the project's developer said Monday.$69.5 million of the financing for the Odeon comes through a HUD backed FHA loan arranged through, and ultimately to the benefit of Iberia Bank. It also benefits from a Payment In Lieu Of Taxes (PILOT) "incentive" agreement issued by the Industrial Development Board last year. This is the latest high-end development in the section of the CBD re-branded "South Market District."

Once complete, the 29-story building will be the latest addition to the half-billion-dollar South Market District, which has transformed an area between Loyola Avenue and Baronne Street once known for blight and parking lots into five blocks of boutique shops and high-end apartments and condominiums.

These projects are eligible for something like $3.5 million in tax credit financing thanks to state laws carried by now City Councilmember Helena Moreno and by State Rep Walt Leger. The development is adjacent to property held by the Landrieu family. While it's true that all of this public investment, including the nearby Loyola Streetcar, has dramatically reshaped the look and feel of a downtown neighborhood, it's difficult to argue that the luxury condos, pied-a-terres, and Airbnb farms being constructed in that neighborhood have done much to make housing more affordable.

A few blocks downtown from South Market along the new streetcar line we find other examples of buildings put "back into commerce" after Katrina through federal grants, loans and tax credits that are being sold off to timeshare operators.

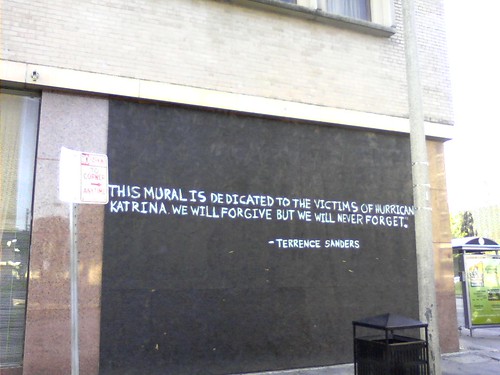

Earlier this year, the council approved zoning changes for the CBD that will make it easier for timeshare companies to operate in most areas. The City Planning Commission’s staff backed the move, arguing in a report that a timeshare “does not possess any more unique characteristics as compared to a hotel, hostel or commercial short-term rental,” which are all permitted uses in the affected CBD areas.In 2009, I happened to snap a picture of a this mural on the side of one of those buildings. Needless to say it is no longer there today.

Now, the owners of other CBD buildings are already marketing their properties to suit this new option. Several buildings, including New Orleans’ oldest "skyscraper," the 11-story Maritime building at 800 Common St., which has 105 apartments, and the Saratoga building at 212 Loyola Ave., with its 155 apartments, could potentially follow suit, according to real estate experts.

Both buildings were recently brought back into commerce by their owner, architect and developer Marcel Wisznia. The Maritime building was renovated in 2010 at a cost of $38.8 million, and the Saratoga a year later at a cost of $41.8 million. Both renovations benefited from federal and state historic tax credits and, in the Maritime’s case, new markets tax credits, which promote investment in low-income areas. Both properties also have mortgages insured by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Last year, Wisznia came under fire from a local housing rights group for converting many of the units into short-term rentals, which it claimed violated federal rules.

"Incentives for developers aren't serving the city." The consultants got that much right. But their report isn't here to condemn the practices that have served us so ill. Instead they ask only that we adjust their "alignment." The objection is not philosophical. It is merely technical. Read past the nonsense about point systems, ignore the song and dance about altruistic goals and the report basically boils down to one core recommendation: Do fewer PILOTs but more TIFs.

Tax Increment Financing is, like PILOT, a scheme by which tax revenue is redirected from the schools and roads and drainage it was meant for. All of these so-called incentive programs starve public services of their dedicated money in one way or another. In the case of a TIF, a portion of the taxes is paid directly to the bank over a period of several years until a developer's loan is paid off. Why the consultants think this is better is anybody's guess.

In any case, we aren't going to "serve the city" any better as long as we remain mired in an outmoded belief that critical public services are best financed through upward redistribution of public resources and delivered as byproducts of real estate projects that primarily benefit the wealthiest interests. Rearranging the tax credits on the deck of a sinking city is not going to solve our problems.

No comments:

Post a Comment