Can you read this?

It says "Help." Or, at least it did once. This is a sidewalk I pass over every day. Sometimes I still stop to wonder who needed help here. I've been thinking about it constantly this week because, well, how can one not? The national spotlight has burned hot on New Orleans this week. It has, for worse and for better, illuminated some of the fading markers of our trauma like this message in the sidewalk here.

To us it is jarring. Not because we've "put Katrina behind us" even if some people do make that assertion. How could we, though? It defines everything about what's become of us since. But because we've lived with its scar so long, we've come to understand that it is just a part of our body now. It's still with us. We've just grown accustomed to having it. The attention this week has caused us to feel it in a way we might not have in a while.

We're not reacting well to that. How could we? The uncomprehending scrutiny of the world outside combines with the avalanche of official bullshit from city leaders to create an echo of that time after the flood when we felt abandoned or betrayed by an entire system at all levels. So while everything this week seems like it is about us, none of it is really for us.

Our friend Adrastos captured much of this anxiety earlier in the week in

a widely distributed post he wrote for First Draft.

People have been in a very tetchy mood here all month. It’s made worse

by all the disaster tourist journalists and carpetbloggers popping into

town, taking our temperature, and putting their own spin on our story.

That makes it their story, not ours. Once again, we live it every day,

they’re just drive-by Katrina experts. Go bug somebody else and leave us

alone.

Can you see it here? Look closely.

I took that photo this week. There's a search and rescue mark on that wall. You might not know if you aren't looking for it. Here. I'll show you same wall in June 2006.

If you've been reading this week, you'll know I've made a project of revisiting the sites of old photos and reshooting them.

Here's the link to all of those posts. This post will be one of them too.

When I started to write about revisiting the rescue marks, I realized after a while that I had already

written a post like this last year. At that time also I was thinking about what the experience of the flood still meant to those of us who lived through the recovery.

Katrina and the flood have formed an indelible mark on our lives. It

is the palimpsest upon which every story about our city today is

written. Nine years later, it is impossible to understand anything

happening in New Orleans without talking about how that thing was made

possible or necessary by Katrina.

So while the flood isn't the first thing on everyone's mind these days, you don't get too far into explaining anything without dealing with the fact of it in some way. After this week, I'm sure we'll declare it's been put to bed entirely. This will not really be true. But in some ways I expect it will feel so. And this can be for the better or for the worse.

Here is

something Troy Gilbert posted earlier this month that got my attention. It's a previously unpublished interview with Chef Greg Picolo about his post-Katrina experiences. There's a paragraph toward the end where Picolo talks about how the flood changed his outlook on civic life to a degree.

Asked how he was changed by the entire experience, the Chef answers

quickly, “That Greg doesn’t live here anymore. Before I led a very

monastic lifestyle. I kind of broke out of the tunnel vision I had

before. Today, I have more of a need to connect with people. I needed to

lose some of my control. I’m easier going. I have zero patience for

bullshit, and now I just don’t get bogged down with stuff.”

I'm certain I am not alone in saying this really hits home. It might be the common denominator of everyone's experience rebuilding New Orleans. When we got back, we were shaken out of our silos. Each of us in some small way at least had to look around to see who our neighbors were. Who else was here? Who could help? How could we help them? Entire new networks were stitched together out of parts that just weren't possible to bring together before.

I wonder, though, if ten years later, we're starting to sink,

bit by bit, back into our own tunnel visions of life in a new New Orleans. As we put the recovery "behind us" is receding

from the tighter cross sectional communities we built during that process a

good idea? Why might this be important?

Well, for one thing, let's take a look at

who does and doesn't think New Orleans has recovered.

According to a survey released Monday by the Manship School

of Mass Communication’s Reilly Center for Media and Public Affairs at

LSU, nearly 80 percent of white residents in New Orleans think the state

has mostly recovered.

But three in five black residents — 59 percent — say it hasn’t.

“White and African-American residents of New Orleans tend to see the

past decade in very different ways,” said professor Michael Henderson,

who directed the survey. “Most white residents think life in New Orleans

is better today — not simply better than the toughest times that

followed Hurricane Katrina, but better than it was before the storm even

arrived. Most African-American residents do not feel that way.”

So that's uncomfortable. At a time when the calendar tells us it might be okay to close the book on "recovery" we're finding that the work is not all done.

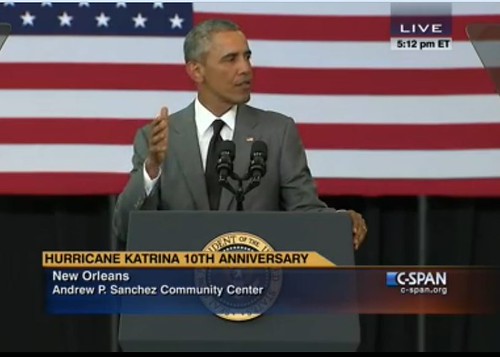

President Obama said as much during his visit Thursday.

So we've made a lot of progress over the past 10 years. You've made a

lot of progress. That gives us hope. But it doesn't allow for

complacency. It doesn't mean we can rest. Our work here won't be done

when almost 40 percent of children still live in poverty in this city.

That's not a finished job. That's not a full recovery. Our work won't

be done when a typical black household earns half the income of white

households in this city. The work is not done yet.

Our work is not done when there's still too many people who have yet

to find good, affordable housing, and too many people -- especially

African American men -- who can't find a job. Not when there are still

too many people who haven't been able to come back home; folks who,

around the country, every day, live the words sung by Louis Armstrong,

"Do you know what it means to miss New Orleans?"

I worry that the class and racial divide in our perceptions of recovery is allowing some of us to sink back into complacency. I worry that even though we've learned to live with the fact of our altered reality, we are in danger of losing its lesson through active denialism.

Former Times Picayune reporter John McQuaid

wrote about this on Medium today.

America is an optimistic nation. It has a short memory. Our political

system and media don’t really learn very obvious lessons that unspool

right in front of everyone’s faces. And so we end up repeating our

errors — at least, some of them — to great sorrow.

Memories, even the painful ones, are what make us who we are.

Eradicating their marks might be an act of optimism. But it can also be a willful negligence of a more chronic condition. Out of sight. Out of mind.

But it would be a greater mistake to lose the expanded sense of community that helped us help ourselves these past 10 years.

On Thursday night, Black Lives Matter co-founder

Alicia Garza spoke to a full house at the Ashe center. The subversive power of active community networks was a major theme of her speech.

Garza ran down a list of threats to black lives — blasting neo-liberals,

the “racist blowback” of President Barack Obama’s election and

reelection and subsequent “bursting of the Obama bubble,” the national

affordable housing crisis, climate change, gentrification and the

literal threats of violence (and many deaths) of blacks at the hands of

white police officers. “The crisis in the Gulf Coast didn’t start when

the levees broke,” she said. “Levees have been breaking for black people

for a long time now.”

Recovery, then, should include a radical shift of power — an economic,

social and political transformation, she said. Black people should seek

new forms of power and learn to wield and execute it differently “than

those who oppress us” while abandoning “solidarity” and instead taking

on “radical conspiracy and collaboration.”

When I heard Garza's speech I took the distinction between "solidarity" and "radical conspiracy and collaboration" to mean the difference between passively receiving a benign official definition of community and actively stretching beyond those limits to create stronger connections.

I also thought about the city's summer long promotion of the term "Resilience" and how impotent the celebration of that buzzword was compared with the countless

citizen directed networks and actions that sprouted up in the wake of the flood. If we lose momentum; if we retreat from those participatory actions and rest on our "resilience" we will move in a direction opposite to what Garza is calling for.

Rather than responding to President Obama's call to finish the work of recovery, we are in danger of sliding into complacency. Because

we are not Kristen McQueary, we should not want to wait for another Katrina to shake us out of that rut. In the next ten years, if we're going to help each other, we're going to have to keep shaking each other awake. And to do that, we'll have to remember some unpleasant things.

Even if we don't always see them in front of us.