Up to 8 percent of the homes in New Orleans would be eligible to be converted into whole-house short-term rentals, in addition to an unknown number of half-doubles and condos, under proposed rules being considered by the City Planning Commission.For an administration aiming to increase the number of annual visitors to 13 million (up from last year's 9 million) by 2018, that is a very strange thing to say. They're goosing the "market" themselves. Also strange is that bit about how the "zoning process" is going to keep everything under control. What they're really looking to do there is bury all objections under a byzantine process.

If every house that under the rules could be rented to tourists in fact became a whole-home rental, there would be about 15,000 of them throughout the city under the density caps included in the proposed rules, according to an analysis by The New Orleans Advocate. That’s out of about 190,000 total housing units counted in the 2010 census.

Hitting that cap is unlikely, though, given that it would require the practice to spread to areas that do not typically attract tourists, such as New Orleans East.

Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s administration did not question The Advocate’s figures, but a spokesman called the analysis “unrealistic” and “unnecessarily inflammatory,” arguing that the market could not support that many short-term rentals and that city officials would tamp down on excessive numbers through the zoning process.

City officials have suggested that the conditional-use process would serve as a check on the spread of whole-home rentals, both because of the time-consuming nature of the process and because of political considerations that might lead the council to reject many such applications.In other words, they don't really expect anyone to apply for conditional use. They expect the innovators to just keep on disruptin'. Also of note is the specific part of town they want to see Airbnbed.

The Landrieu administration has estimated that only about 150 applications could be processed each year.

At that rate, it would take 20 years just to process the whole-home rentals that already are available in the city.

It seems unlikely that the city would in fact engage in a two-decade process to issue permits for all those rentals — or that owners would agree to stop renting their properties for years while they seek permits.

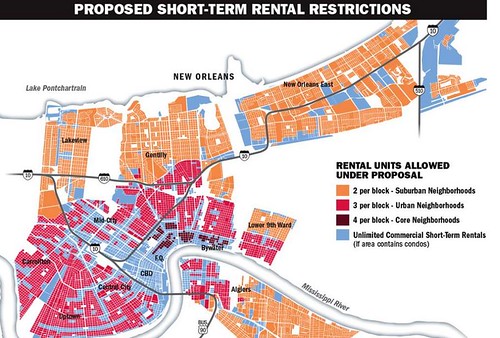

The number to be allowed is capped based on the zoning of the neighborhood: Four would be allowed in residential blocks in the historic core neighborhoods of the French Quarter, Marigny, Treme and Bywater; three per block in the “historic urban” residential areas that dominate south of Interstate 610; and two per block in the more suburban areas near Lake Pontchartrain, in New Orleans East and in much of Algiers.Ah yes the old "Sliver By the River." Ten years ago, the value of the "historic core neighborhoods" there was being reconsidered, not only in terms of their value to the tourism industry, but also in terms of the city's overall sustainability.

There would be no per-block limit in areas not zoned residential, such as the Central Business District.

The Advocate’s analysis calculated the total number possible based on the number of residential blocks in each of the zoning categories.

About 7,000 of the possible short-term rentals would be allowed in neighborhoods where there’s already been a proliferation of such rentals, primarily those along or near the river. As with the citywide numbers, that would represent about 8 percent of the housing units in those areas, according to Census Bureau statistics.

Yet by that point, (developer Joe) Canizaro was admitting that it was inevitable that he would duck the tough call and not prohibit low-lying neighborhoods from rebuilding. He was a white man leading the redevelopment of a city that was two-thirds black. Of the 353,000 people living in a part of the city that flooded, 265,000 were black.

“Unfortunately, a lot of poor African-Americans had everything they own destroyed here,” he said. “So we have to be careful about dictating what’s going to happen, especially me as a white man.”

Race was a vital element of the Great Footprint Debate — and for me (also white), it turned a hard decision into an impossible one. For decades, racial covenants and discriminatory lending policies in the city meant black homeownership had been restricted to only a few neighborhoods. Barbara Major, the co-chairwoman of the mayoral panel on which Canizaro served, noted that there was a reason why so many black families lived in New Orleans East, as she did, and in other low-lying parts of the city.

“Black people only moved there because all the high ground had been taken,” said Major, who is black.

John Logan, a sociology professor at Brown University, broke down by race (and other factors) the makeup of the blocks that Canizaro’s experts wanted to leave uninhabited. They were talking about land that housed 80 percent of the city’s black population.

What do you tell those residents, many of them longing to return home? “Look, sorry, we know that was the only land where you could pursue the dream of homeownership, but you’re going to have to find another place to live?” New Orleans East was mostly swampland in the 1960s when developers started building in the area. By 2005, it was home to 96,000 people, or one-fifth of the city’s population, and it was where much of the city’s black middle and professional classes lived, along with a large portion of its black elites.

The Great Footprint Debate at that time was more about deciding who could come back at all than where in town they ought to live. But there was an element of environmental responsibility that lent it a patina of legitimacy among the apolitical. In this 2015 article, Richard Campanella summarizes the recommendations of planners and risk managers inevitably frustrated by the political realities of the post-Katrina scramble back to high ground.

An intense debate arose in late 2005 over whether low-lying subdivisions heavily damaged by Katrina’s floodwaters should be expropriated and converted to greenspace. Most citizens and nearly all elected officials decried that residents had a right to return to all neighborhoods. Planners and experts countered by explaining that a population living in higher density on higher ground and surrounded by a buffer of surge-absorbing wetlands would be less exposed to future storms, and would achieve a new level of long-term sustainability.

Despite its geophysical rationality, “shrinking the urban footprint” proved to be socially divisive, politically volatile, and ultimately unfunded. Officials thus had little choice but to abrogate the spatial oversight of the rebuilding effort to individual homeowners, who would return and rebuild where they wished based on their judgment of a neighborhood’s viability.

Unsurprisingly, this somewhat laissez-faire approach (nudged along by other policy decisions such as school charterization and a drastic reduction in the number of public housing units available) has supercharged the process of gentrification in the "core historic neighborhoods" over the past decade. This is from a 2015 Advocate report.

So, in the long run, what we've ended up with is kind of the worst of both ends of the Great Footprint Debate. On one end, we're still struggling to serve vast swathes of slow-to-recover, low lying neighborhoods. Try taking a bus out to New Orleans East, for example. Or better yet, pick up some groceries in the Lower Nine.. you know.. without stopping at CVS. On the other end, the skyrocketing cost of housing in the "sustainable" parts of town is a continuing obstacle to low income residents.Drive through the Marigny and Bywater neighborhoods and you’ll be hard-pressed to find an unoccupied home, save for a few straggling properties being fixed up for sale in a super-hot real estate market.But just across the Industrial Canal, it’s a different story in many places. There, you’ll find a scattering of houses looking like the teeth of a jack-o’-lantern on broken streets lined with weed-choked lots.While the region as a whole has emerged from the decade since the 2005 flood with an impressive 94 percent of the population it had before the storm, a closer look at the recovery shows an uneven picture.Core neighborhoods are booming, having lured both returning New Orleanians and newcomers alike, while some parts of the city still seem barely unchanged since late 2005.While the changes are far less severe than they might have been had city leaders heeded calls to abandon some neighborhoods altogether in the months after the storm, they still point to a challenging road ahead for some areas.

And on top of it all, we're tossing a highly questionable approach to dealing with short term rentals. Here is the map that accompanied the Advocate's analysis of the proposal before the City Planning Commission.

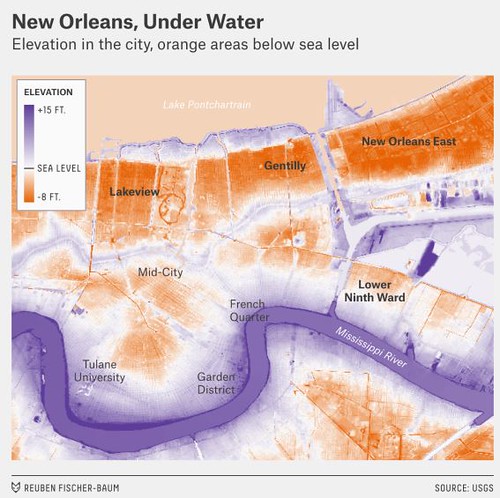

And here is an elevation map from the 538 article by Gary Rivlin I quoted from earlier.

Generally speaking, the higher the ground, or if you like, the more sustainable the living space, the more short term rentals the city wants to put there. In other words, the parts of the city we've long been told are the places we should concentrate our population are the very places the mayor's people are planning for no one but tourists to actually live. In the long run, we're right back at where we always worried we would be. The city we've rebuilt isn't really for us.

I'm typing this now as the District C community budget meeting is going on in Algiers. I just happened to notice on Twitter that the mayor is being asked about this very thing.

Frederick: "How would you feel if you had... volunteered your blood and sweat and finances to rebuild houses after Katrina?"— Jessica Williams (@jwilliamsNOLA) July 7, 2016

Frederick: (and) how would you feel if the city had a plan where they tried to increase shortterm rentals & take away affordable housing— Jessica Williams (@jwilliamsNOLA) July 8, 2016

Frederick: "I would feel like it was a slap in the face."— Jessica Williams (@jwilliamsNOLA) July 8, 2016

I haven't read his response yet but I'm guessing he'll talk about the five year

The city's affordable housing plan builds on "extensive, community-based" work by housing advocates and Foundation for Louisiana. Those groups in December unveiled the HousingNOLA plan for adding 5,000 affordable housing units by 2021, including 2,000 rentals, 1,500 home purchases and 1,500 units for people with special needs.

So the plan is to add 5,000 "affordable" units by 2021. It doesn't say whether those 5,000 will be on high or low ground but, ok, assume 5,000 in another five years. If, in the meantime, we're opening the spigot on a potential 15,000 short term rentals, what good do those 5,000 units really do? What, exactly, are we expecting the market to ultimately support here?

No comments:

Post a Comment